Scattered petals, a mixture of performance, movement and song, an archetypal morality tale … I used to loathe this kind of theatre. It was a bit like modern dance – I found it pretentious; its lack of narrative, dramatic tension and meaning made me anxious.

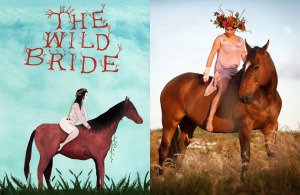

Last night’s performance of The Wild Bride at Kneehigh Theatre’s Asylum venue started out a bit like that. The bride in question’s foolish father makes a pact with the devil but as is usually the case with fairy tales it all happens at lightning speed – the father is tricked almost immediately and before you know it his innocent daughter has been betrayed and left in the woods to fend for herself.

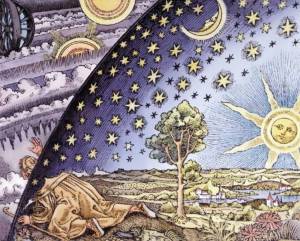

I was on the verge of ho-hum territory when I realised I was being drawn in to the magic of the experience. The space itself is enchanting – a nomadic cathedral-like tented structure, consisting of twin half-domes and a vaulted roof – and the performances are captivating – particularly those of the three women playing the bride at different ages, who powerfully express the daughter’s pain, her descent into primordial chaos and her joy.

I was on the verge of ho-hum territory when I realised I was being drawn in to the magic of the experience. The space itself is enchanting – a nomadic cathedral-like tented structure, consisting of twin half-domes and a vaulted roof – and the performances are captivating – particularly those of the three women playing the bride at different ages, who powerfully express the daughter’s pain, her descent into primordial chaos and her joy.

It’s an emotional, rather than a dramatic narrative – an elemental journey to the wilderness and back. And to express that kind of archetypal journey you need a different type of language – not the language of conventional theatre, not discourse, not argument but a somatic language, a language that speaks to our mysterious inner rhythms, what neuroscientist Antonio Damasio calls ‘the music of core consciousness’.

I suspect that’s why I used to find modern dance and this kind of performance so problematic – because I couldn’t respond to it with my intellect, my chief modus operandi. But really, who wants to respond to art with the part of their brain that is more at home theorising and debating or the part that would rather be sitting cross-legged in the meditation room? Who’d choose Damien Hirst’s Pharmacy – an installation based on a concept so banal Hirst must have come up with it in the time it takes to dissolve a soluble aspirin in water – over Goya’s The Dog, included in my last post?

Accustomed to using my intellect as a defence mechanism it took me a while to find a way to connect with art, rather than trying to appreciate what I thought I ought to appreciate. For me, it was all about letting go of preconceived ideas about what art, dance or theatre should be and discovering what happened when I allowed myself to just take in what was in front of me.

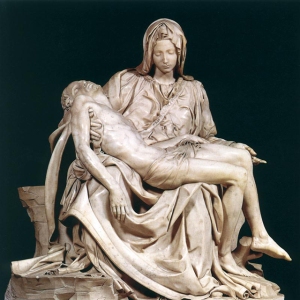

I was often surprised by my response. For instance, I’d always thought I preferred abstract to figurative art but Michelangelo’s Pietá in St Peter’s Basilica moved me to tears, and I was so transfixed by Arnold Bocklin’s The Island of the Dead in the Metropolitan Museum of Art I had to keep returning for another look.

Letting go of preconceived ideas doesn’t mean you leave your critical faculties at the door. I find much modern dance boring, too cerebral or too concerned with the contortionist aspects of movement and there’s a lot of truly dire physical theatre about, the kind that relies on cheap gimmicks and infantile humour. But there are a few companies who do it well – Kneehigh, dreamthinkspeak, Frantic Assembly – combining design, theatre, music and movement to create a beguiling, mesmerising and visceral experience that can create echoes in places we’ve long forgotten.

To finish here’s a clip of an old favourite dance piece of mine – the Rambert Dance Company’s Ghost Dances: